Politics: How does the topic influence the way material is taught

January 30, 2018

A harsh opinion, a destructive ideology, or a questionable comment; all things a parent would dread to hear coming from someone in a position of power, like a teacher.

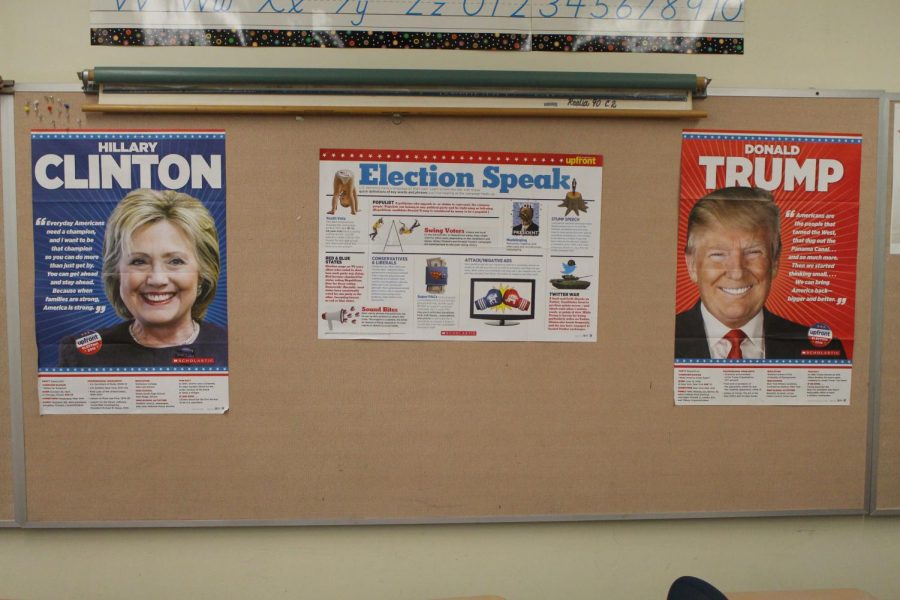

In a place like a classroom, somewhere literally built to be a place of influence and learning, nobody wants to think that something as personal as political affiliation could be impacting a student’s education. It is very troubling to imagine that something as shaky and subjective as political views could be affecting what we consider impressionable minds, used to learning curriculum. Frankly many people, students, teachers, and parents, would agree that political affiliation shouldn’t have a firm hold in the classroom if it’s not necessary for a students schooling. This is an argument that people from all sides of the political spectrum can appreciate, as many see this as an important issue.

History teacher Amanda Williams seems to think so, even having only been at Gresham since the beginning of the school year.

“The best thing for a teacher to do is to present both sides of the argument,” Williams said. “Especially in social studies classes.”

She understands that when it comes to examining history and social relationships, bias seems to be inherently part of the equation. In her classroom, she is sure to clarify both sides of the issue, and she always explains the context of all biased historical documents.

Similarly, history teacher Dan Anderson feels the same way about the idea of political influence in education.

“I think a lot of it comes from mutual respect,” Anderson said.

Anderson knows what it is like to be the odd one out, and he feels it is important for all student opinions to be respected.

“That teacher needs to understand that 50% of kids will disagree with their opinion,” Anderson said.

Something that is not often thought about when issues like these are brought up is how a student may feel when it seems like their personal views are seemingly directly persecuted by someone they may respect. Not only does this make a learner defensive, it can make them feel like anything the teacher says could have some kind of hostile undertone, whatever it may be.

Needless to say, this does not create a space ideal for learning in the slightest, so is there anything that can be done from the inside to prevent something like this?

Unfortunately, it might not be as simple as we might want it to be. Differences in what constitutes crossing the line, and an educator’s way of projecting their ideas are things that may complicate the process, to say the least.

For one, it is difficult to determine what is an intentional swaying of a student’s opinion, and what might just be a teacher expressing their views.

This leads to another issue: at what point would it be considered infringing on a person’s individual rights, like freedom of speech and opinion, to say limit what teachers can say, be it in a classroom or otherwise?

“I think that disagreement is always going to arise, because we’re human people,” English teacher Crystal Hanson said.

It could be more difficult than one may think to differentiate between an actual destructive intention and simply an expression of worldview.

Luckily, it seems like the extreme of this issue is something we have not had to deal with yet at Gresham, but it is important that issues similar to these and of significant importance like these are greatly considered before something does in fact come about. Especially when the outcome could be as personal as the influence of a student’s own political views.