Free Speech Frenzy

April 20, 2019

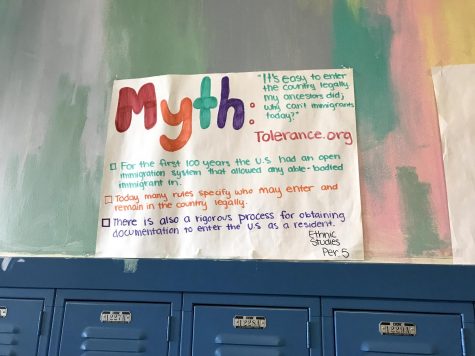

A couple of weeks ago, the ethnic studies class put up posters debunking immigration myths. The class put a myth, from Tolerence.org on each poster and below this placed a fact, proving each myth wrong. These posters did not stay up for long. In fact, nobody knows where they are now.

The class, according to the ethnic studies teacher Mark Adamski, put up the posters without permission, thinking that they would create inclusivity for the students that have to deal with this issue. As a sign of approval, anything displayed on a wall on campus must get a stamp from the activities office. These posters went up without one.

“[The posters] might have been too provocative,” Adamski said when asked about why they were removed.

The class tried again, this time asking the administration for approval. They received approval, but with the restriction that they are up for only two weeks. Some would think by taking down these posters would also be restricting freedom of speech.

The US Constitution guarantees free speech but absolute free speech stops as students walk in the school doors. School policies at Gresham-Barlow, Reynolds, David Douglas, and Centennial school districts all say the same thing: students can express themselves if they do not disrupt others or their educational process.

There are dozens of posters and signs around the school that do not have administrator permission and are not taken down. Why are these posters allowed stay up, but the immigration myth posters taken down? The administration insists the ethnic studies’ posters were taken down because they did not have approval, not because of their content. However, many disagree.

School policy says that any signage at school cannot contain bias or prejudice. But bias is often very subjective.

“Bias can be taken either way. Everyone has bias to some degree,” sophomore Josh Chandler said.

Gresham High School, like Reynolds, has designated the activities office, which at Gresham consists of Ty Gonrowski and Tahana Young, to sign off on posters and any other displays put up by anyone associated with the high school. Both say they have no clear guidelines on protocol or steps to determine if a sign is reasonable or not; however, they do fall back on the E.D. code, which in the section entitled “Freedom of Expression” states that any displays or productions cannot be disruptive of one’s educational process and cannot be biased or prejudice in nature.

Gonrowski and Young both judge if bias is present. But is it safe or acceptable to only have two minds, and two perspectives deciding what is allowed on the school walls and presented to the student body?

“I do not feel like two people can decide what’s bias because again their own personal opinions go into this,” senior Jasia Mosley, who helped put up the original immigration myth posters, said. When asked for an interview to discuss the situation, Gonrowski respectfully declined.

In the 20th and the 21st century, five major supreme court cases about freedom of speech in schools have influenced schools in the United States. One of the biggest cases was Tinker vs. Des Moines.

During the Vietnam war, high schooler students in Iowa protested the Vietnam war by wearing black armbands. The school prohibited this, but students still proceeded with their protest. One student, 15-year-old John Tinker was suspended, but this did not stop the movement. Other students rose up and protested along with him. Most of these students were suspended, so the Tinkers sued the school. The case was sent to the supreme court and the Des Moines school lost 7-2. The opinion of the court was delivered by Judge Abes Fortas.

According to Fortas, quoted on education.law: “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate … School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are ‘persons’ under our Constitution”.

In some cases, students are even prosecuted when posting anything regarding school online, outside of school property. Sharing thoughts are harder to do without any school consequences. To be informed of the world and to have a good sense of what is happening is important to be able to contribute to society as future adults. Suppressing a child’s voice in a place of learning and growing to create a safer environment could cause more harm than intended.

According to The Atlantic, John Tinker’s little sister, Mary Beth Tinker, who also participated in Iowa Vietnam protest said, “If we do not encourage young people to use their First Amendment rights, our society is deprived of their creativity, energy, and new ideas. This is a huge loss, and also a human rights abuse”.

Assistant principal Jason Bhear said that the school wouldn’t allow posters showing symbols of hate like confederate flags or swastikas. But these symbols of hate cannot be compared to something factual and true posted on campus, like the immigration myth posters.

Adamski doesn’t think the posters were taken down to restrict free speech. He believes that they may have interrupted the educational process for some students, but in a good way. Thinking and voicing our thoughts freely, may come along with discomfort but will deliver confirmation for others and one’s own thoughts rather than being told what to believe.

“White people do not like being uncomfortable. They have a history of being comfortable. So, of course, they want to continue to not see the real facts,” Adamski said.

During the commotion of the immigration posters, another poster stating, “Why be racist, sexist, homophobic or transphobic when you could just be quiet?” was put up in the hallway by the cafeteria.

Other posters were soon placed around the first poster, stating their own opinions on the matter. Some slightly agreed, while others opposed. As no permission was made for any of the posters, they had to be taken down, though some walking past the posters could have felt unsafe while reading the messages.

The posters placed in the cafeteria represented an unintentional interruption of the educational process which could have lead to possible uncomfortable emotions.

However, we shouldn’t hide pressing issues so we can secure the emotions of others. Placing relevant information that allows students to think should not be limited by time, according to senior Mosley.

“It’s extremely frustrating that we even have to have a time limit [on the posters] because there is no time limit on this issue. It’s still going, it’s continuing it’s growing and students at our school are still being affected by it. I think it’s important that we still have these up,” senior Mosley said.