Holocaust survivor

January 15, 2020

Never again. Two words, one phrase; a phrase dedicated to genocide remembrance, civil rights activism, and more recently, school shootings and the fight for gun control. Genocide, not often the topic of conversation, due to it being an uncomfortable subject, is something many remain uninformed on.

According to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, genocide is the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group,” through killing, bodily or mental harm, prevention of births, the transferring of children to another group, and/or inflicting inhumane living conditions.

The word genocide came about after World War 2 when the entire world found out about the atrocities committed against Jewish people. Genocide is a word used to describe the end result of slow seeping discrimination. It was only in 1948 that the United Nations declared genocide to be an international crime.

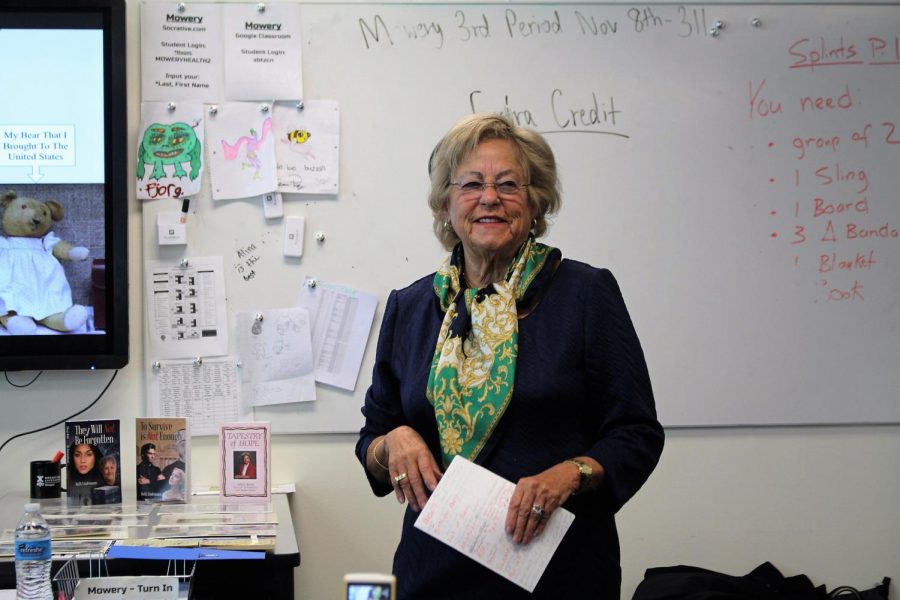

Rachel Fortgang, global perspectives and English teacher, in collaboration with Mark Adamski, head of the social science department, recently worked together to bring in a Holocaust survivor to speak to students about her first-hand experience of the beginning stages of the Holocaust.

Ruth Lindemann, a 1951 GHS graduate, was born in 1933 in Vienna, Austria. A month after her fifth birthday, Germany began to occupy Austria. At the time, Vienna was the most “technologically and culturally advanced country at the time,” according to Lindemann. Her family, all Jewish, witnessed

first-hand discrimination and oppression.

“Vienna was a big cultural center. You wouldn’t expect that these criminally insane people would actually take over. But they did. And from one day to the next, our friends were our enemies. It was legal. Just because something is legal, does not make it moral,” Lindemann said.

Nuremberg laws were implemented to dehumanize, segregate, and exterminate Jewish people. Houses were searched regularly. Jewish people weren’t allowed to have radios, bicycles, pets, and valuable jewelry. Jewish people weren’t allowed to work or marry Germans. Many were forced out of their homes and forced into concentration camps, and many were deported. The acts of terror committed against Jewish people were methodical and planned.

“The sheer grotesque [nature] of what happened fascinates people because it was so systematized,” Fortgang said.

Leaving the country proved to be incredibly difficult. Many Jewish people wanted to leave but according to Lindemann, one had to have a sponsor to leave. They needed permission to enter a country, and not many countries were willing to take in Jewish people. In addition, they had to have the proper paperwork.

Meanwhile, Lindemann and her family lived in fear. “You were not supposed to be out after dark if you were Jewish…every night I heard gunshots. We knew people were being killed,” she said.

Lindemann and her family were able to successfully leave Austria after they received an affidavit, an official written statement made under oath, from an American cousin.

Students who heard Lindemann speak on November 8 expressed their awe.

“Hearing the story from someone who experienced it made me see things differently. As she put her emotion into the story, it’s almost like I felt it too. I could imagine her story and all of her emotions that went with it,” senior Shianne Haddad said. “She showed me a different perspective of the Holocaust. She made it seem so real rather than hearing it from a secondary source. This is why it’s important to learn about genocide; because history repeats itself and we can notice the signs and prevent it from happening.”

Oregon Senate Bill 664, passed on June 10 of this year taking effect on July 1, 2020, will require schools to include genocide and the Holocaust into high school curriculum. According to the bill, the purpose of it is to make students aware of genocide, to gain respect for cultural diversity, to gain insight into the importance of human rights, and to recognize patterns.

“I think we all are sort of naturally desensitized toward mass death, which is why we actually have to make an effort to kick in our compassion centers and actually try to imagine it because it’s all abstract until it’s my family or my friend,” Fortgang said.

Although the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide is in effect, many genocides since the Holocaust have occurred. Some of the largest genocides in recent history include the Cambodian genocide, the Armenian genocide, the Rwandan genocide, and the current Myanmar genocide. Most of these genocides were systematic and followed similar patterns to the Holocaust.

The world said “never again”, and yet, again and again, it has happened, and many in the world have stayed silent, even though this is a humanitarian issue.

“We’re all the same inside. We all have to eat and sleep and breathe air and take care of our children. There’s very little difference between people,” Lindemann said.